The above image shows potential temperature trends. Four of the trends are global ones and one trend is based on Arctic (64°North-90°North) data:

- The red line is a polynomial trend based on 15 years of Arctic data (2009-2023).

- The green line is a linear trend based on 1880-2023 global data.

- The yellow line is a linear trend based on 2009-2023 global data.

- The light blue line is a 10-year moving average (trailing), based on global data.

- The dark blue line is a polynomial trend, based on 2015-2023 global data, showing global temperatures catching up with the Arctic rise in temperature.

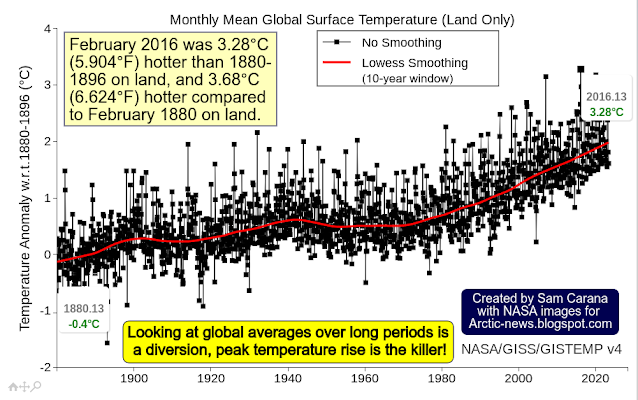

Note that the above image uses annual anomalies from 1951-1980. Recent posts show that, when adjustments are made for an earlier base, for ocean air temperatures and for higher polar anomalies, the 2023 anomaly could be as high as 2.5°C from pre-industrial and when using monthly data, the anomaly could be as high as 2.73°C from pre-industrial.

Temperature rise hits Arctic most strongly

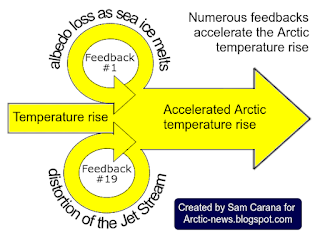

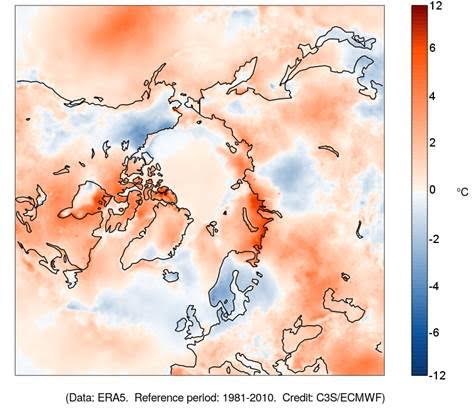

Due to feedbacks such as sea ice loss, the temperature rise is felt most strongly at higher latitudes North, as illustrated by the three images below, again using a 1951-1980 baseline.

The image below shows the December 2023 temperature anomaly.

The image below shows the 2023 temperature anomaly.

The image below shows how the temperature rise has unfolded from 2000.

Over the next few years, the temperature rise in the Arctic could accelerate even more strongly as a result of crossing of two tipping points, i.e. the Latent Heat Tipping Point and the Seafloor Methane Tipping Point, as illustrated by the image below, from an earlier post.

Arctic sea ice extent

|

| [ ocean stratification, from earlier post ] |

Slowing down of AMOC and cooling due to heavier melting of Greenland's ice is causing less ocean heat to reach the Arctic Ocean, while a huge amount of ocean heat is accumulating in the North Atlantic, as it did in 2023. A large part of this heat in the North Atlantic can also be present underneath the sea surface.

These developments occur at the same time as ocean stratification increases (see above image) as temperatures rise, as more freshwater enters the ocean as a result of more meltwater and of runoff from land and from rivers, and as more evaporation takes place and more rain falls further down the path of the Gulf Stream, all of which can contribute to formation and growth of a cold, freshwater lid at the surface of the North Atlantic.

|

| [ cold freshwater lid on North Atlantic ] |

The danger is that huge amounts of ocean heat can abruptly get pushed into the Arctic Ocean and that the influx of ocean heat will destabilize hydrates contained in sediments at the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean, resulting in eruptions of huge amounts of methane.

|

| [ click on images to enlarge ] |

(1) surface wind and temperature (-3.6°C or 25.4°F at the North Pole)

(2) surface wind

(3) wind at 700 hPa

(4) wind at 250 hPa (Jet Stream) and

(5) ocean currents at surface and wave height.

And ominously, the daily sea surface temperature reached a record high on January 31, 2024, when the daily sea surface temperature reached 21.10°C, higher than the peak of 21.09°C reached in August 2023 and much higher than the 20.99°C peak reached in March 2016.

|

| [ The buffer is gone - Latent Heat Tipping Point crossed ] |

|

| [ potential methane rise, from earlier post ] |

|

| [ from the Extinction page ] |

The image on the right illustrates how a huge temperature could unfold and reach more than 18°C above pre-industrial by 2026.

As a rather sobering footnote, humans will likely go extinct with a 3°C rise and most life on Earth will disappear with a 5°C rise, as illustrated by the image below, from an earlier post.

|

| [ from earlier post ] |

Climate Emergency Declaration

Links

• NASA - Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) Surface Temperature Analysis

https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp

• Ubiquitous acceleration in Greenland Ice Sheet calving from 1985 to 2022 - by Char Greene et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06863-2

discussed at facebook at:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/arcticnews/posts/10161223121909679

• Danish Meteorological Institute - Arctic sea ice volume and thickness

https://ocean.dmi.dk/arctic/icethickness/thk.uk.php

• Cold freshwater lid on North Atlantic

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/cold-freshwater-lid-on-north-atlantic.html

• Latent Heat

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/latent-heat.html

• Pre-industrial

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/pre-industrial.html

• Could Earth go the same way as Venus?

• Extinction

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/extinction.html

• Climate Plan

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/climateplan.html

• Climate Emergency Declaration

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/climate-emergency-declaration.html